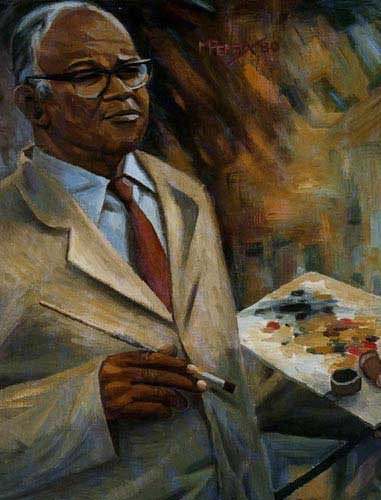

Remembering a South African painter and writer who remained in the country and used paint brush and a pen to fought the apartheid regime

It has been observed that his work only really emerged from provincial obscurity as apartheid began to crumble. Although he had exhibited for many years, and had been included in The Neglected Tradition exhibition in 1988, he only really came to the attention of a largely white art-buying public when the Everard Read Gallery in Johannesburg exhibited his work in 1991. While the exhibition was a great success, it had a darker aspect which exposed mounting dealer opportunism in relation to the work of previously-marginalised black artists. A dealer by the name of Hans J. Weber had earlier visited Pemba in Port Elizabeth and purchased 178 of his paintings for R4 000, which he then sold to the Everard Read Gallery for an undisclosed sum. These were framed and sold for about 125 times what Pemba had initially been paid for them. As a compensatory gesture, the Everard Read Gallery paid Pemba 10% of the sale price of each picture.

The 1991 exhibition had foregrounded Pemba’s oils, but it was not until 1993 that the showing of a cache of his earlier watercolours at the Highbury Gallery in Port Elizabeth revealed his even more impressive artistic powers. He was first tutored in watercolour by Ethel Smyth in 1931 at the University College of Fort Hare, and subsequently in 1937 by Professor Austin Wintermoore at Rhodes University. Pemba attributed his accomplishment in watercolour to Wintermoore’s insistence on sound draughtsmanship. The watercolours painted between c.1933 and c.1947 are among his very best works. This raises interest around the choice that he made, allegedly prompted by Gerard Sekoto (qv.), to switch to oil painting.

There is disagreement about where this crucial meeting of Pemba and Sekoto took place. Although himself a watercolourist of note, Sekoto held that it was too delicate for South African subjects, which he felt demanded a more robust medium. He also drew Pemba’s attention to the greater saleability of scenes of the ‘locations’ with the emergence of the ‘township’ genre. He also mentioned that white buyers placed a far higher premium on oils.

Pemba’s images of indigenous South Africans of different cultures fit well within the genre of the ‘native study’ which was also pursued at this time by his contemporary Gerard Bhengu (qv.), as well as by white artists such as Barbara Tyrrell (qv.), Irma Stern (qv.) and Neville Lewis (qv.). While white artists went on formal expeditions to paint ‘the natives’, it is interesting to note that Pemba also felt compelled to mount an exploration of South Africa for this same artistic purpose, receiving an amount of £75 from the Bantu Welfare Trust in 1944 to cover his travelling expenses.

Certain works in the Campbell Smith Collection reveal Pemba’s expert handling of watercolour, while others indicate how he first effected his shift to painting in oil. Zulu woman – unfinished symphony (1941), (plate 46) shows his initial broad underdrawing with underpainting in delicate washes in certain areas. Darker, more solid tones are selectively placed over these in order to give a sense of form. The sensitive face – the psychological fulcrum of the whole work – is the only ‘finished’ area of the painting, yet one senses that any further additions would have been superfluous. Xhosa woman smoking a pipe (1945), (plate 42) shows Pemba’s tentative exploration of the oil medium, using it in thin layers to achieve luminous effects on a primed board, much like watercolour. He initially resists the possibilities of thicker paint and the use of white as an additive colour at this time, until his mastery of oil becomes more accomplished and deft, as in his urban landscapes Gelvandale (1957) (plate 49) and New Brighton (1960) (plate 48).

Pemba’s Retrospective Exhibition at the Iziko SA National Gallery in Cape Town in 1996, with a scholarly catalogue as well as the subsequent publication of two biographies by Sarah Hudleston and Barry Feinberg, finally achieved the aim of giving his life and work a truly national profile.

Hayden Proud

George Pemba's works remain among my best favorites of all time. I can easily relate to the pieces he painted and even feel the emotions of the characters. While many of his peers used words to tell the story of that time back in the turbulent days under institutional racism, Pemba painted his experiences and reflections.

ReplyDeleteI totally agree with you. He incredibly occupied a special place in the historical art canon and I so wish I had atleast one of his original signed and dated masterpieces.

ReplyDelete