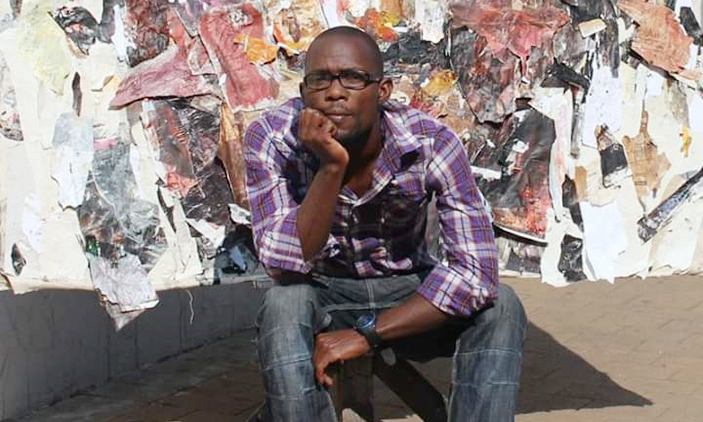

Remembering the most remarkable collagist, Benon Luaaya

Ugandan-born collage artist, Benon Lutaaya draws inspiration from his own life experiences and explores issues related to homelessness, isolation, fear and identity. He works with paper collage, acrylics and mixed media to construct fragmented, fragile and visually rich collages that speak to his continuing journey of creativity through vulnerability. Following his most recent exhibition at GIBS, which we brought to you a few weeks ago, The Journalist’s Khehla Chepape Makgato speaks to Lutaaya about life as an artist, his obsession with hard work and being an entrepreneur.

What are the origins of your interest in the cultural meanings of collage, and how did you come to evolve the wide-ranging, interdisciplinary approach to collage?

First of all, I believe that, our life itself is a collage of a series of experiences. My interdisciplinary approach to collage was born out of my total lack of financial resources to afford proper art supplies as well as to support myself when I started out professionally. This naturally, necessitated improvisation, resourcefulness, perseverance and a further two remarkable by-products. One of these is creativity and another is sensitivity. Both attributes define my work.

The waste paper material communicates the vulnerability of human life. And through my collage techniques, I’m able to comment and raise many fundamental questions about the complexity of human conditions today.

Some of your images explore strong facial shapes or gestures: they command a presence, like statues or they seem to represent suspended structures. What role does “gestures” and “human faces” hold in your images?

There is a very logical thought process to the way I work with human faces and gestures. Dealing with a portrait subject is dealing with my own feelings and emotions. Each gestural mark, a line here, a dark or light there you see in my work is very intentional and achieved through a deeper connection with my inner self.

Do you focus on a theme or topic throughout or you deal with multi-themed series?

I could be dealing literally with the same subject matter, and perhaps the same commentary, but how I tell it, is ever evolving, maturing, and improving. Those who have watched and followed my work since 2011 will tell you, it has matured and improved a lot.

However, I do deal with other subjects too. I have painted animal subjects. And throughout my university training all I did was landscape painting. I never dealt with portraiture.

I would love to think its early days. I’m NOT going to be exploring the portrait subject all my life. This is my fourth full year as a professional. So, I still have a long way to go in as far as learning my trade is concerned.

Can you please take us through the process of your creation and the inspiration or influence in your work?

I would say, and this is what most people do not know. I struggle to paint, but I try every day. It’s very frustrating, but exciting for a reason.

When I’m painting, I use the waste papers I gather from the streets as my palette. They serve as my surface from which I mix colours. When I’m not painting, I have got plenty of them.

Instead of cleaning them out of the studio, they become an important material for my collage artworks. Basically my collage art is a by-product of my painting process.

When you arrived here in Johannesburg, South Africa you were unknown and struggled like any other young African artist, can you tell us about your experiences and challenges to becoming famous, established and collected?

Famous?

Not yet. I know it’s possible, but there’s still a very long way to go. There is no universal answer. And what has worked and works for me may not work for somebody else. It all depends on this question! Why did you become an artist? Lots of young artists will give you many academic and complex answers that conform to how they were taught at the art school.

Personally it was for a simple reason to change lives not literally but in a big tangible way. And that had to start with my own life. To achieve that, I learned very quickly and early enough that, I had to work bloody hard and be exceptional at what I do. Then, equip myself with capabilities to apply myself out there as a business entity.

You seem to be working independently without having signed with any gallery but you instead collaborate with any gallery you deem fit, how did you develop this approach and what are the challenges and pleasures of this approach?

Yes, it’s safe to say I work independently, but I associate and identify with Lizamore and Associates gallery. We have a really good work relationship.

In the beginning, I had to think deep and develop an innovative model that would guide me to the top where I’m the chief decision-maker, the captain of my career ship while able to work in tandem with the traditional gallery establishments without being answerable to them.

It was never easy, it has never been easy, but it works, it has worked for me, and it’s extremely rewarding. I believe, what distinguished me from most young African artists is that, I made a decision to take responsibility for my career. Inside the studio, I was and still am a total artist. Outside of it I chose a different identity-some sort of a start-up entrepreneur.

I don’t believe in the notion that, this makes you a commercial artist. In my case, it makes me better and keeps me grounded and focused while respecting my creative core values, vision, aesthetics. Being an “artrepreneur” though, is a different kind of responsibility that demands as much time, effort, innovation, and dedication as your studio creative work. It’s tough. Selling art is a tough business. Ask any gallerists, they will tell you. Most artists can’t apply themselves in the real world beyond the canvas, and that’s the source of the difficulties of our job. I had to teach myself and I still do!

Looking at your work both technically and conceptually you’ve grown in leaps and bounds from the first time I spoke to you in 2011 when you first arrived at Bag Factory Artists’ Studios, what is the secret behind this significant growth?

It is absolute obsession to work hard and hunger to grow, to scale new heights with your work. Most artists need mentors in order to break into the industry both to establish themselves and to enter the art market, but no one mentored me in regards to breaking into the market. It was a personal instinct, drive and desire to be successful and independent. I never had an opportunity to meet someone that had done that for themselves to teach me. It was pure research. And understanding, and realising that I can treat my job as a start-up entrepreneurial project.

But from a technical and conceptual perspective, being at the Bag Factory was the best thing to have happened to me. I benefited and still benefit from the amazing community of artists there.

Very few people realise that; Patrick Mautloa has been the hugest influence on my technical, artistic development. I admit it to many people, but they doubt me, simply because they don’t notice elements of his work in my work. Perhaps that’s what makes him exceptional. He guides me from my perspective, not his.

How would you advise young artists or ordinary black artists who are struggling to make some ends meet with their art career?

First rule, they must be sure its art. Art doesn’t do well with uncertainty. If they are really convinced, it means they have to take responsibility. They are responsible for their careers. Not that top critic from the university, or that discerning gallerist even though it’s important to seek advice.

They must create art that exploits their creative abilities and strengths in relation to either their understanding of the world and not the rule-book of the institution they are coming from. They must get rid of the institutional lot as fast as possible. Once they identify their strengths it becomes a little easier.

Next is hard work to technically and conceptually improve their strengths. We all make careers from our strengths, not necessarily what academic elitists contextualise as cutting-edge within the confines of postmodern art.

To make ends meet starts with good art, never mind the debate of what makes good art. Just get the best out of you. And it comes with independence of thought and hard work.

This article was first published on The Journalist publication in 2015.

Benon Lutaaya died in 2019 in Johannesburg aged 34.

Comments

Post a Comment