Tales of the humiliated people kept alive by Sizwe Banzi Is Dead

The Market

Theatre stages a modern classic play entitled ‘Sizwe Banzi is Dead’. The

new-generational embodiment of Sizwe Banzi is Dead, starred by contemporary

South African actors Athandwa Kani (John Kani’s son) as (Styles and Bantu) and

Mncedisi Baldwin Shabangu as (Sizwe Banzi

and Robert Zwelinzima) hits the Market Theatre stage after almost four decades.

The production which was pioneered through collaboration between the white

South African playwright Athol Fugard and the black actors John Kani and

Winston Ntshona in the 70s is one of the great South African classics in the

theatre landscape locally and internationally.

Sizwe Banzi

is a chronicle of the dehumanizing treatment of South Africa’s black population

under apartheid. The play starts in a small photography studio called Styles

Photography studio and follows a comic story of a man who is willing to keep

himself alive but his name dead in the manner of speaking. His quest to survive

without his real passbook tells a potent parable of the persistent brutalities

of life under the Afrikaner regime. The passbook was a symbol of inferiority, a

tool the apartheid regime used to control not only the movements but the minds

of the black people. Even Nelson Mandela had such mystery when he was arrested

on 5 August 1962 in Howick, KwaZulu-Natal, using the alias David Motsamai.

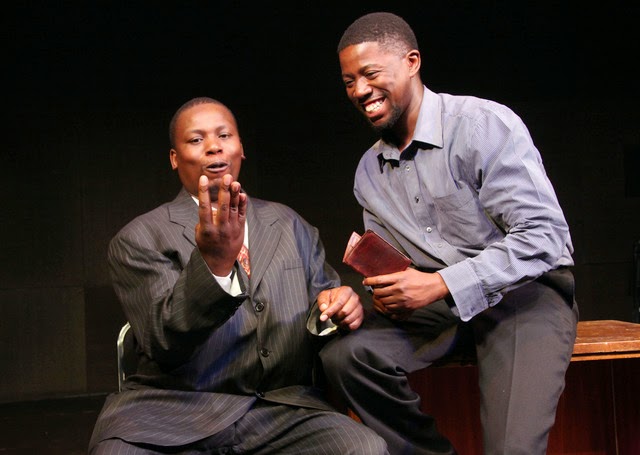

Baldwin Mncedisi Shabangu as (Sizwe Banzi and Robert Zwelinzima) and Athandwa Kani as (Styles and Bantu)b from Sizwe Banzi Is Dead. Publicity Picture (Web)

Atandwa Kani walks

onstage in the role of Styles, just after telling us a long and highly

entertaining story about the years he worked in a South African Ford car

factory and how disappointed he was after having cleaned up the place for a

high ranking executive from America who only briefly visited and inspects the

place. The Ford car factory is where the then actor and present director Dr.

John Kani of the play worked as an engine assembler in 1960s.This

autobiographical sketch of Kani, senior is a testament of how far the South

African theatre has come.

Exploited as

he was, Styles enduring his humiliations with absurdity and self-esteem,

finally has revenge on his bosses by deliberately mistranslating in Xhosa their

orders to his fellow factory workers. Subsequently he decided to open and run

his own photography studio, taking formal photographs for special occasions —

weddings, funerals, birthday parties and family cards. He went to a friend of

his called Dlamini, who already owned a funeral parlor, explained to him the

whole idea and Dlamini said to him “Styles! This is your chance my son, don’t

let it pass, grab it.”

He does not

only take pride in being his own boss but he also shares that pride with his

audience. He describes his profound desire in quitting this exploitative labour

and becoming his own boss as a photographer of black South Africans as

something he did for the interest of his people. He believes that his work is a calling. “You

must understand one thing,” he tells us. “We have nothing except ourselves, we

own nothing except ourselves. This world and its laws allow us nothing… There

is nothing we can leave behind when we die except the memory of ourselves”. He

is resolute that his profession is one that could afford ordinary people snapshots

of memorial site that could otherwise not be provided by the apartheid regime.

The play

takes off in a startling turn when a smartly dressed black man comes in to have

his photograph taken. His name he says, as if not quite sure of it himself, is

Robert Zwelinzima and the story of how he arrived at Styles’s studio forms the

second half of the play. It turns out that he has assumed a dead man’s

identity. The play reminds us that his is story of honest rural black man

battling a dehumanising bureaucratic regulation, who cannot find employment,

because he does not possess a valid passbook, and must assume the identity of a

dead man to survive and provide for his family.

Mncedisi

Shabangu, in a role as Sizwe, narrates a love story of a man whose family is

physically miles apart but passionately close to his heart. He portrays a role

where a man is concerned about the wellbeing of his family back home despite

being dislocated from his home by a quest for survival. He epitomizes a man who

cannot be easily swallowed by the big city thus forgetting that he is married

with four children. He frequently sends a letter to his wife and reads it to us:

“Dear Noweto, for the time being my troubles are over. Christmas I come home.

In the main time Buntu is getting me a lodger’s permit. If I get it you and my

children could come here in Port Elizabeth. Spend the money I sent you

carefully. If all goes well I will be sending you more and more every week from

now. I do not forget you. Your loving husband, Sizwe Banzi” This is a

historical testament that a simple letter helped so many African families to be

tied together. A letter was only a medium of communication for blacks in

aparthied.

As Sizwe,

Shabangu, flicks in his cream white double-breasted suit, it is all smiles and restless

eyes. Whether he is posing cunningly for Styles’s camera or confusedly

journeying his way home after a night at the shebeen, his role has the thorough

physical grace of a typical clown. He talks a twisted language and emphasizes

every word he says to prove his intelligence after Bantu teased him of not

knowing his way back their two roomed house.

Shabangu furthermore

makes us notice the harshly worn dignity underneath Sizwe’s ridiculous

exterior. When Buntu begins his campaign to persuade him to assume a new

identity, Sizwe adheres with muted firmness to his own. Is a man without his

own name a man at all? “I’m afraid,” he confesses. “How do I live as another

man’s ghost?”

Bantu, who

knows well how the government has mercilessly stripped away from blacks their

human rights, has a quick answer. “Wasn’t Sizwe Banzi a ghost?” As Charles

Spencer, a theatre critic puts it “The play becomes a powerful attack on the

apartheid pass laws that determined where black people could and couldn’t live

and work.”

Sizwe Banzi

is the play of the forgotten people, faded dreams, and a humiliated population.

It has restored the liveliness of the South African humility, especially the

black people during the dark ages of apartheid.

Review by:

Khehla Chepape Makgato, Newtown, Johannesburg, November 2014

Comments

Post a Comment