A 'harvester' of ancient knowledge whose name says it all, Daniel 'Sefudi' Rakgoathe

Daniel Sefudi Rakgoathe was born on the 25th of February 1937 in Randfontein, Johannesburg. His middle name 'Sefudi' means 'harvester' which is given to a person who harvested more than anybody in the village per season. His father Ephraim was a school teacher and his mother Phani Rebecca completed the then standard six, which according to their times was like matric of those years. He called his father a 'rolling stone' because they never lived in one place for a long time. I suppose in his own words, Dan would say 'Tate olle hlogo ya kgaka' - loosely translates a person disappears from a place that no longer gives him warmth and comfort many times. Kgaka (Guineafowl) is a bird symbolic of human effort at survival. It is said that when a country looses its fertility, the guineafowls are the first birds to disappear. Eating head of Guineafowl may literally mean you keep on moving from one place to another.

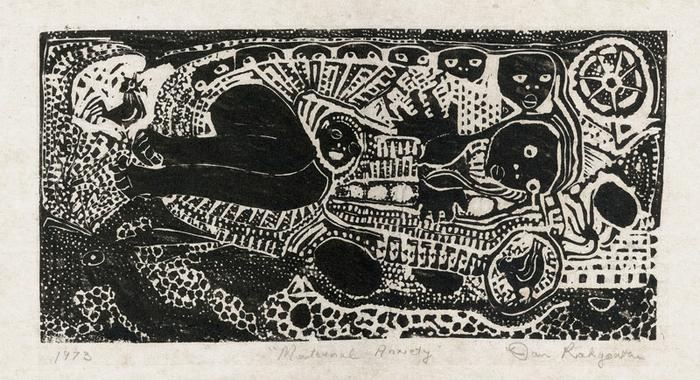

Plate 192, Maternal Anxiety, 1973

When Dan was little he liked drawing but his parents could not afford to buy him materials and paper. This did not stop him from expressing himself artistically. He would frequent a fireplace to collect burnt wood particles which he used them as charcoal sticks to draw all over his body to avoid getting a hiding for drawing on the walls of his house.

From Standard VI, Rakgoathe was taught art by Mr Maseko, one f the first black handicrafts teachers in South Africa. Rakgoathe completed his junior certificate and in 1959 completed a two-year primary teachers training program at Botshabelo Training Institute. In I960, with the help of the Reverend Henneck Seloane, Rakgoathe was able to attend Ndaleni Art Teachers Training College. When he completed the course he taught at a primary school in Moroka, Soweto, in 1961. The following year he taught an at the Normal College at Botshabelo Training Institute.

In 1963 he taught at a primary school in Pretoria and in 1964 was a school board secretary at Dennilton near Robertsdale for a short time. He returned to teaching at a high school in Dennilton and remained there until 1967 when he enroll as a fine arts student at UNISA. To satisfy the practical requirements for the degree, Rakgoathe decided to move to Rorke's Drift where he was the first full-time student in the fine arts section, In 1969, when he completed the course at Rorke's Drift, Rakgoathe was appointed cultural officer in the Johannesburg City Council and took over Ezrom Legae's position at the Jubilee An Centre. When Jubilee closed down, in the early 1970s he continued teaching at Mofolo Ans Centre until 1976 when he enrolled in the Fine Arts course at the UFH. Rakgoathe received credit for first year courses completed at UNISA and in 1978 he was awarded a BA(FA) degree. The following year he was awarded a BA (FA) (Hons) degree and then enrolled for a Master's Degree.

However, he returned to his former post at the Mofolo Art Centre and did not complete the course. In 1981 Rakgoathe was awarded a Fulbright scholarship and in 1983 completed an MA degree in African Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles, USA. On his return to South Africa in 1984 Rakgoathe took up a post at the Bophuthatswana College of Education. He left there in 1986 and returned to live in Orlando, Soweto. Rakgoathe passed away in 2004. (sahistory.org.za)

In all his work Rakgoathe tried to capture what he described as the ‘Spirit of Creation’. Rakgoathe’s vision and approach is well illustrated in Maternal anxiety (plate 192), a linocut of 1973. It is a vision not of the outer world but an inner one. The mother is seen as an archetype rather than as an individual, the other stylised figures extending this vision of an inner world. The theme of anxiety is intensified by the compressed space of the composition, akin to the compressed space of the womb; this is echoed by the foetal position of the main figure. Heightening the sense of anxiety in this haunting, obsessive image is the ghost-like figure in a complementary position to the figure of the mother. The power of this work is also discernible in the fact that the beautifully designed decorative elements are not merely ornamental but form a vital, integral part of the whole. (Joe Dolby)

Rakgoathe’s primary interest was in the linocut, so his etching Initiation ritual (plate 31) is, in terms of its medium, fairly unusual. This work appears to reflect many aspects of his Northern Sotho or Pedi heritage. In this image, a centralised female figure stands with both hands raised. She looks down at her breasts, which produce life-giving milk. Her facial features suggest an African mask. Above her float three circular shapes which seem to be the moon in its various phases; a reference, most likely to the monthly cycle of menstruation. In front of her stands what appears to be a masked female initiate who holds her transparent belly. A crowd of ritualistic beings in the background looks on.

Plate 31, Initiation Ritual

The central figure in Initiation ritual is virtually identical to that in Rakgoathe’s linocut entitled Rain Queen (1973) (Fig. 6). This print was based on the legend of Modjadji which Rakgoathe had learned from his grandmother. This Rain Queen is a fertility figure, an earth mother from whose breasts flow nourishment for all living things. Rakgoathe was highly attuned to the feminine, and guardedly admitted once to his belief that in one of his previous lives he had been incarnated as a young girl who had died at the age of thirteen. To this he attributed his awareness and sensitivity to the special talents, needs and problems of women in the world.1

Rakgoathe’s etching Initiation ritual can thus be read as a celebration of the centrality of the feminine role in the cycle of life. While pubescent boys undergo a ritual circumcision so that they can enter into adulthood, in the case of Northern Sotho and Pedi girls the initiation takes longer. The initiation takes place when the young woman experiences her first menstrual cycle, and this fact is divulged to the senior women. Each girl undergoes her own initiation, but has to attend and take part in the rituals of a number of other girls as part of this process. This whole process is supervised by full initiates, who are ultimately under the authority of an old woman who has been chosen by the initiate as her ritual ‘mother’. This role cannot be taken by the girl’s natural mother, who is forbidden to enter the ‘hut of seclusion’ and who cannot intervene during some of the trials and tribulations that the initiate is put through by her elders. Much advice concerning sexual activity, her future relations with men and proper behaviour to towards her elders is dispensed at this time. When she has been through the number of required ceremonies, she is finally presented to the most senior woman in the district to be beaten with a stick as a sign of her new status as a woman. Rakgoathe’s Initiation ritual is a work of technical complexity and layered mystery that allows us a glimpse into the sacred arena of Northern Sotho and Pedi belief and tradition. (Hayden Proud)

Sources: www.revisions.co.za

www.sahistory.org.za

See Donvé Langhan. 2000. The Unfolding Man: The life and Art of Dan Rakgoathe. David Philip Publishers. Cape Town. p.130-132.

For a more detailed account, see E. Jensen Krige and J. Krige. 1943. The Realm of a Rain Queen: A Study of the Patten of Lovedu Society. International African Institute/ Oxford University Press. p.110-114.

Comments

Post a Comment